No man’s body is as strong as his appetites.

~ Tillotson

slip:4a1551.

No man’s body is as strong as his appetites.

~ Tillotson

slip:4a1551.

How can you effectively and gracefully end a conversation while maintaining its value and mutual appreciation?

Understand the balance between leaving a conversation fulfilled and seeking more.

Craig and Jesse discuss the complexities of ending conversations, beginning with the idea that most conversations naturally conclude due to external factors like time constraints. Craig notes that in many casual interactions, such as those at events or in public spaces, the end is often dictated by circumstances rather than a conscious decision.

I know I didn’t even try to get everything [from a conversation] because I know I can’t get everything. So it’s somehow finding a balance between: “Okay, my cup is full. I should really move away and just revel in what I have.” Finding a balance between that, and just going to the well until the cup comes up empty. I think that’s probably the compass for how to find a good ending.

~ Craig Constantine (4:25)

They explore the notion that it can be beneficial to end conversations while they are still engaging, rather than waiting until all topics are exhausted. Craig shares his experiences from recording podcasts, where he finds it challenging to end on a high note, emphasizing the importance of planning and strategies for graceful conclusions.

We’re here looking for ways to make conversation more alive […]. I’ve adopted this strategy of, stop eating when I want to eat a little bit more. stop talking when I want to talk a little bit more. Stop training, moving around and exercising when I want to move a little bit more. So that I’m actually left in the wanting of it […]

~ Jesse Danger (5:13)

They also touch on the distinction between enjoyable and uncomfortable conversations. Jesse brings up the idea of stopping activities, such as talking or training, while still wanting more, to maintain a sense of aliveness and enthusiasm. The conversation shifts to practical strategies for ending conversations, including honesty about one’s need to leave and expressing appreciation for the interaction.

Jesse references Peter Block’s concept from the book “Community,” suggesting that when ending a conversation, participants can share what they gained from the interaction, fostering a sense of closure and mutual respect. This approach, they agree, can enhance the quality and impact of the conversation.

Takeaways

Ending conversations naturally — External factors often dictate the conclusion of casual interactions.

Ending on a high note — Beneficial to conclude conversations while they are still engaging.

Challenges in planned endings — Strategies and planning are crucial for graceful podcast conclusions.

Distinction between conversation types — Different approaches are needed for enjoyable and uncomfortable conversations.

Maintaining enthusiasm — Stopping activities while still wanting more helps preserve a sense of aliveness.

Practical strategies — Honesty about the need to leave and expressing appreciation can aid in ending conversations.

Concept of shared appreciation — Participants can share what they gained from the interaction to foster closure.

Spontaneity in conversation exits — Creative and spontaneous actions can make leaving a conversation smoother.

Balancing conversation engagement — Finding a balance between getting enough out of a conversation and not exhausting all topics.

Resources

Community by Peter Block — Discusses the importance of commitment and shared appreciation in group settings.

The concept of “single-serving friends” from the movie Fight Club — Refers to brief, context-specific interactions that end naturally.

ɕ

(Written with help from Chat-GPT.)

The most important preliminary to the task of arranging one’s life so that one may live fully and comfortably within one’s daily budget of twenty-four hours is the calm realization of the extreme difficulty of the task, of the sacrifices and the endless effort which it demands.

~ Arnold Bennett

slip:4a1201.

There are thousands hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.

~ Henry David Thoreau

slip:4a939.

Picasso observed that, “inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” Inspiration has to find you in the midst of your practice.

Let’s say that I enjoy painting. When I find myself painting, I usually find myself happy. I love the feeling of setting down my brush after having worked out some little problem in a painting. And so, I decide I’m going to paint regularly.

Or let’s say I enjoy sailing. I love the adventure, or the wind in my face. And so, I decide I’m going to sail regularly.

Or, running, writing, movement, music … your choice.

But without concrete plans, and clear processes, I will never actually do the practice. Friction, followed closely by excuses, will sap my momentum. If I’m to be a runner, my shoes, clothes, music or whatever I need— Those things must be in place. For any practice there are some things which you will feel must be in place.

The processes that I’m imagining, which remove friction and enable my practice, have a steady state. For my process, what does “done” look like? It looks like me sailing so often I can’t even remember not sailing all the time. Or it looks like me running and jumping and playing so often that my body is a comfortable place for my mind.

Matthew Frederick, the author of 101 Things I learned in Architecture School, makes this point:

True style does not come from a conscious effort to create a particular look. It results obliquely—even accidentally—out of a holistic process.

This point about a holistic process—the idea that mastery isn’t some higgledy-piggledy mish-mash of throwing things together—is an idea I’ve held dearly for a long time. Every single time that I’ve decided to take a process, and repeat it in search of understanding, the learning and personal growth has paid off beyond my wildest dreams.

I’m a process process process person. The second time I have to do something, I’m trying to figure out how to either never have to do that again, or how to automate it. (And failing those two, it goes into my admin day.) Random activity, powered by inspiration works to get one thing done. But inspiration doesn’t work in the long run, and it won’t carry me through my practice.

Instead, I want to know what can I intentionally do to set up my life, so that I later find myself simply being the sort of person who does my chosen practice? I want to eliminate every possible bit of friction that may sap my momentum.

There’s a phrase in cooking, mise en place, meaning to have everything in its proper place before starting. The classic example of failure in this regard is to be half-way through making something only to realize you’re missing an ingredient and having to throw away the food. Merlin Mann, who’s little known beyond knowledge workers, has done the most to improve processes for knowledge workers and creative people. I’m not sure if he’s ever said it explicitly, but a huge part of what he did was to elevate knowledge workers and creatives by cultivating a mise en place mindset.

And don’t confuse “process” or a “mise en place” mindset with goals. Forget goals. Focus on the process, and focus on eliminating friction.

To quote Seth Godin:

The specific outcome is not the primary driver of our practice. […] We can begin with this: If we failed, would it be worth the journey? Do you trust yourself enough to commit to engaging with a project regardless of the chances of success? The first step is to separate the process from the outcome. Not because we don’t care about the outcome. But because we do.

And I’ll give my last words to Vincent Thibault, author of one of my favorite books:

That is how we are still conditioned socially as adults: Do, achieve, produce results, instead of be, feel, enjoy the process. Quantitative over qualitative. We are obsessed by performance and “tangible” results. But that is one of the great teaching of Parkour and Art du Déplacement: That the path is just as enjoyable as the destination; That sometimes it is even more important, and that oftentimes it is the destination.

ɕ

Information competes for our conscious attention: the web of thoughts with the greatest activation is usually the one where we direct our attention. The calmer our mind, the fewer thoughts we generate in response to what happens in the world—and the greater the odds that intuition will speak to us.

~ Chris Bailey from, The science of how to get intuition to speak to you – Chris Bailey

slip:4uaite1.

I’m not sure if I truly remember the following story, or if I simply heard it told so many times and subsequently retold it so many times that I believe I saw it first hand, but here it is in first person regardless.

Sitting in an enormous church service early one morning, two parents down front where having increasing difficulty with a precocious young child. With each noise, question, request, and pew kicking, the parents were taking turns playing the, “If you don’t be quiet…” game. The massive church was known by all to have a well-appointed “cry room” at the back complete with a view of the proceedings, amplified reproduction of the goings on, double-pane and mostly scream proof windows, games, rocking chairs and so forth. Meanwhile, in the main hall, everyone could hear the “if you don’t be quiet…” game escalate to defcon 5: “If you don’t be quiet, I’m taking you to the cry room.” The opposing forces countered with a volley of indignation at being forced to… “That’s it!” And the patriarch hoisted the youngster and performed the mandatory “excuse me pardon me excuse me…” incantation across the pew, and started up the aisle with a writhing 3-year-old in Sunday’s best. From the moment of hoisting, the winding-up siren of shock and horror got up to speed until said child was screaming. “I’LL BE QUIET! I’LL BE QUIET!!” The minister had paused, as the father strode briskly for the doors at the back. Hundreds of people sat silently as they passed through rear doors—the child’s screaming dropping instantly in volume as the door swung shut. “I’LL BE QUIET! I’LL BE QUIET! …i’ll be quiet!” At which point, as far as I could tell, everyone collectively giggled at the humor of it all.

While one part of my mind wants to be touring the facility and taking up slack, the petulant child is not to be taken on by main force. When it’s in the mood, the child part can be a source of great power and inspiration. (Apropos, the quote sticking up from the Little Box today reads: “Genius is the power of carrying the feelings of childhood into the powers of manhood.” ~ Samuel Taylor Coleridge) The inner-child mind has its own agenda and demands its outlets too.

ɕ

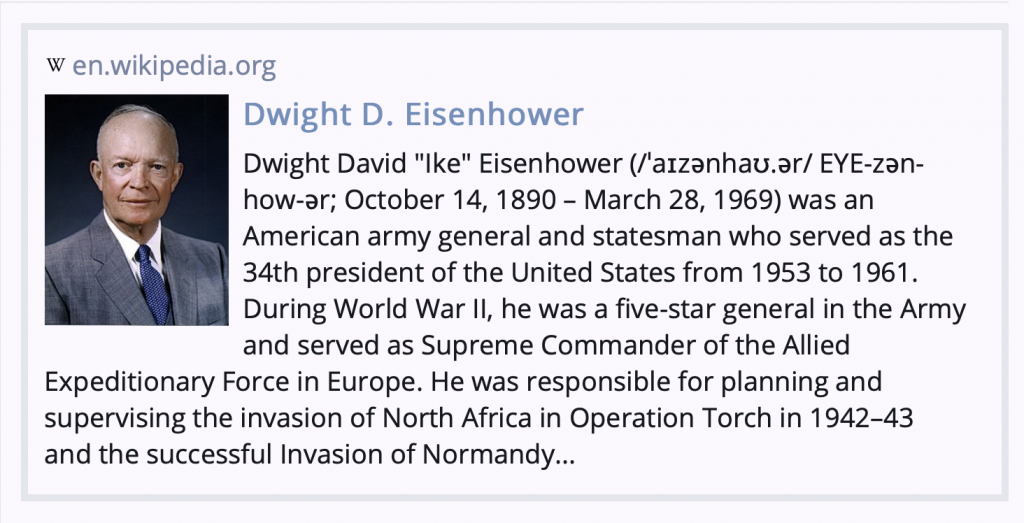

This is a standardized way to present a preview of a URL. Instead of just showing a URL, like this:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwight_D._Eisenhower

It can be presented as a “onebox,” like this:

That’s just a screenshot from a system which is able to do oneboxing. The magic is that when editing, (wherever you are editing,) you simply paste in a raw URL and the oneboxing is done automatically by the system.

It’s based on the Open Graph Protocol (OG). Facebook started this as a way to get sites on the open web to provide software-understandable, summary information. It took off everywhere because it’s just downright awesome.

A web site includes information stuffed out of sight, in the source HTML of the page. Software can fetch the URL, notice the OG information and craft a meaningful summary. This grew into the idea of presenting a single box summary—”one boxing”—of a URL if it has OG information.

When something doesn’t onebox as you expect, how would you figure out which end has the problem? (Was it the end serving the URL content that doesn’t have OG data? Or is the end fetching the URL that couldn’t parse the OG data?) So someone wrote a handy tool that lets you see what (if any) OG data there is at any URL you want to type in:

ɕ

When you recognize that it is actually impossible to do work tomorrow, then you know to stay with your work until something starts to take form. Today is the only day you can ever work, and once you see this truth, he is defeated.

~ David Cain, from The Four Horsemen of Procrastination (and how to defeat them)

slip:4urate2.

Is Burnout one of the Horsemen? Because that’s the one who defeats me every day.

If I could just convince myself that today was enough.

I’ve not the slightest idea what work-life balance is.

ɕ

These people are, effectively, hiding behind a wall. They are passing up more difficult work for the easy work — sharing or “liking” photos, retweeting, commenting on someone’s wall. These are activities which can serve a purpose, but they are poor substitutes for the real thing. It’s like saying Splenda is the same thing as sugar, tofu is the same thing as real meat, or Red Lobster is a good place for…a red lobster. It’s not the same thing. Not even close.

~ Brett McKay from, How to Build Meaningful Relationships | The Art of Manliness

slip:4uaoai2.

There is a fine line between using social media (and other technology conveniences) to increase the number of people I can keep up with. Dunbar’s Number is often pegged at about 100 or a bit more. I definitely agree that there’s a trade off between how many people I can maintain relationships with and the quality of each relationship. I find the hardest part is when a relationship gets asymetric — when the other person isn’t able to commit as much time — eventually it’s time for me to stop putting in the effort; Eventually it’s time for me to stop trying, and instead to let another person settle into the social space in my universe.

ɕ

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

~ Alfred Lord Tennyson

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

slip:4a320.

Read all the books! Gee… about a hundred books on my to-read pile, where should this one go now that the pre-order wait is finally over?!

ɕ

My guess is that we have all experienced this combination of effortlessness and effectiveness at some point in our lives. While we are completely absorbed in chopping and sautéing, a complex dinner simply assembles itself before our eyes. Fully relaxed, we breeze through an important job interview without even noticing how well it’s going. Our own experiences of the pleasure and power of spontaneity explain why these early Chinese stories are so appealing and also suggest that these thinkers were on to something important. Combining Chinese insights and modern science, we are now in a position to understand how such states can actually come about.

~ Edward Slingerland from, Trying Not to Try – Nautilus

slip:4unaiu1.

ɕ

On 05/07/13 09:15, Michael Tiernan wrote:

> “What is the UDP three way handshake?” He said he was wondering how many people would catch the question’s trick.You send three UDP packets in three different directions, then shake the hand of the person next to you.

~ Robert Lanning from, «https://lists.lopsa.org/pipermail/discuss/2013-May/018116.html»

ɕ