Rest stop somewhere in virginia. Thats 11, swap drivers n back on road!

ɕ

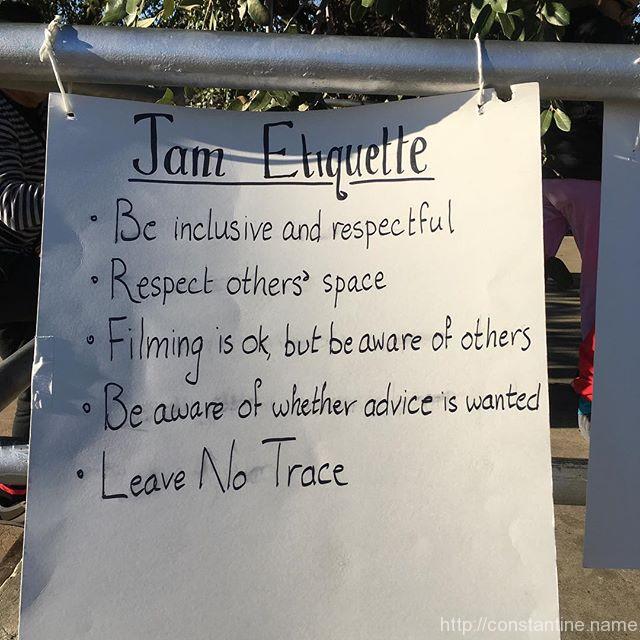

Parkour, Art du Deplacement, Free Running

Rest stop somewhere in virginia. Thats 11, swap drivers n back on road!

ɕ

From the medial rotation of the ilium creating the lateral fascial line and allowing single leg stance to the abduction of the foot’s 1st ray creating the spiral fascial line and lateral fascial line allowing the stability for a rigid lever – everything – I repeat everything favors locomotion – and we need to train the body as such.

~ Emily Splichal from, From Primal to Bipedal | Why we need to get off the ground and walk more! – Barefoot Strong Blog

slip:4ubafo1.

ɕ

All coaches carry out their role based on combination of their experience, knowledge, values, opinions and beliefs, likely with most unaware that they are doing this at all. This melting pot of factors amounts to what can be described as the coach’s philosophy. The question is – do you actually know yourself well enough to understand how these elements are combining to produce your own philosophy of coaching? Do you understand what your core coaching approach and methods are?

~ Dan Edwardes from, A Philosophy of Coaching – Dan Edwardes

slip:4udaai1.

ɕ

With the foot as the only contact point between the body and the ground – much of this “noise” enters our nervous system through the feet. If this foot “noise” is tuned out or unable to be sensed by the nervous system inaccurate movement patterns and delayed time to stabilization (i.e. injury) is the result.

~ Emily Splichal from, How “tuned in” is your nervous system? Advances in barefoot science.

slip:4ubaho1.

ɕ

This series covers all the physical things I’ve discovered which make light-weight traveling easier and more fun. (My thoughts on the philosophy, etiquette, and mindset of traveling are in a separate series.) This series of posts is only meant to give you ideas; I certainly don’t expect you use the exact same solutions. For me, the challenge was not to pack as light as possible, but to pack as light as is reasonable.

I’ve read countless articles on travel, written by everyone from ultra-light hikers to seasoned business travelers. Sometimes, I stumbled over useful ideas and then figured out how to apply them. At other times I went searching for a solution to some specific problem I was having. Over the years, I’ve come up with a collection of items, and related tips and tricks, that I find extremely useful.

It’s obviously important to know what to pack, and to be able to pack well. But I believe the most important part of traveling “light” is developing two habits: unpacking and reviewing. Unpacking ensures I’m always ready, and reviewing ensures I’m always improving. The next two parts of this series will go into these two habits.

But first, why travel lightweight? Why not simply grab the largest bag I have, stuff it with everything I might need, and head out the door? Why spend time and money fiddling with travel gear and solutions? I found my answers to those questions by sorting out the following: I’m most free when I have just the clothes on my back, but I will be unhappy, stressed, or in physical danger when I don’t have whatever-it-is that I happen to need. So at the most basic level, packing light is simply the balance of freedom versus preparedness.

There is also a deeper mental level to that balance. Do I feel free and relaxed, or am I worried? For me, it turns out that simply packing more things does not make me feel more prepared or relaxed. Rather, it’s the idea that I know I am prepared which enables me to be comfortable.

Clearly, the less I have to carry, the easier physically are my travels: In a packed car, my bag can fit on my lap. On a bus, it fits in the over-head, where it’s handy through the trip. On a plane, I can travel with just a carry-on-bag, saving me time and money on checked baggage. It’s also easier to not unpack — to just live out of the bag at my destination. It’s quicker to settle down in the evening, and quicker to pack out in the morning. It’s even easier to keep track of my stuff the less of it there is.

Certainly, there are lots of challenges and trade-offs with traveling light. It is not all champagne and roses. But by investing the time to solve problems and get better at the process, I’m able to have a lot more fun. So my challenge was to pack as light as I can, and still have everything I need.

My first task was then to figure out, “What exactly do I need?”

The more I dug into these ideas, the more I realized that the only way to know I was prepared — to truly feel prepared — was to thoroughly examine what I was packing and carrying. I wound up asking myself a litany of questions and exploring the answers and solutions: Why am I uncomfortable right now? What could I have brought that I could use right now? I never used this thing-i-packed, so why did I bring it? I’m exhausted after carrying my pack all day; Why does it weigh 30 pounds?

This process of examining all my worries, habits, and situations led me to search for solutions. My habits of unpacking and reviewing, which I mentioned at the beginning, are the result of all this questioning and refining of my travel gear.

Along the way, I learned to not pack based on fear or uncertainty; To not pack anticipating everything that might go wrong. Instead, I learned to prepare only for the scenarios that matter — safety items, spare cash, medication. I also learned to feel comfortable in knowing what I could obtain at my destination if things didn’t go according to plan. This became a sort of “anti-packing,” where I learned what not to pack.

Eventually, I wound up with “systems”, or “kits”, for just about everything. A sleep system, in one stuff sack, that has everything I need to sleep on a bare floor. A bathroom kit, in one zipper-bag, which has everything I need for bathing, shaving, etc. A medical/urgent kit (the “m’urgency” kit) that has what I frequently use, plus what I feel is sufficient for common urgencies.

The more I tuned my gear and systems, the easier packing became. These days, I don’t grab my toothbrush out of the bathroom, find my razor, and wonder what soap may be at my destination; I pick up the small, black, zipper-bag that is my bathroom kit. If I might be sleeping on the floor I grab my sleep system. I always grab the m’urgency kit. I grab the clothes I want, and a stuff sack to pack them. I add in various other things, (described in coming posts,) grab my favorite backpack, stuff the contents, and go!

If you really want to get a feel for how much your packing improves, try doing a “test packing” as a starting point for future reference. Note the time, and go pack for a 5 day, 4 night Parkour trip. Let’s presume mild weather, sleeping indoors but on a bare hardwood floor. Let’s say you will be training 3 of the days. Pretend you have no idea what the host conditions are, but assume you have access to a bathroom, shower, wifi and whatever electricity outlets you are used to. (Dealing with not-your-usual electrical systems is a post in this series.) When you are ready to walk out your door, note the time again. Now weigh your stuff and write down the time it took to pack, the weight, and maybe some notes about how you’d feel carrying all that stuff while trying to board a bus, a plane or hop in a car.

Now, as you put everything away, imagine dropping all that on the floor at your host. What if they have to move it while you’re out for the day? Is their dog/cat/toddler going to get into your stuff? Maybe also note your worries: I don’t have a sleeping bag or pad for sleeping on a floor! How do I dry my hair? Look at all these clothes! What if this trip had been to a place with weather extremes, say, you had to train outdoors in freezing temps? What if you knew you’d be video recorded during one of your training days? What if your destination had different electrical power? What if someone threw, or sat on, your bag?! What if… What if…

Recall the two habits I mentioned: unpack and review? You have just done your first unpack and review after an imaginary trip!

ɕ

~ Sensei Wirth

If you want to go east, go east. If you want to go west, go west.

If there’s somewhere you need to be, you need to start walking.

~ uncertain; possibly Lao-Tzu

Each of those quotes expresses a certain commitment to beginning; to taking action; to moving in a direct way. But what really is commitment? I thought I knew what commitment was, until I started to think deeply about it. Now, I’m uncertain.

There are some things to which I am deeply, unshakably, committed; Take breathing for example. At first glance this seems trivial since it’s a physiological imperative managed by the body. But if I imagine a scenario where someone is trying to prevent me from breathing, I can easily imagine myself consciously acting — wildly, vigorously, berserk even — to achieve the goal.

What would it mean to be that committed to something of my own conscious choosing?

What does it mean to “be committed to” a new habit?

Sure! I’m committed! I like this new idea — this new habit. I’m going to really stick to it! I have goals, and a plan. Let’s do this!

…and a month later the habit is nowhere to be seen. Does that failure mean I was actually not committed when I thought I was? Did my commitment evaporate over time? Are there degrees of commitment? Is there some minimum level of commitment necessary at the beginning to achieve certain goals? Does commitment need occasional inputs of energy to keep it going, like a spinning top? Or is commitment a simple binary — yes, or no?

Perhaps understanding commitment would be easier if I tried to untangle a simpler type of commitment. What does it mean to “commit to” a physical action in the very near future?

This jump scares me. But I know I can make it; I’ve definitely jumped this distance successfully many times. I know there’s value in doing this jump. I should do this. I want to do this! Okay, I’m committed! I’m ready! Here I go! abort! ABORT!!

What happened? I thought I was committed? Was I lying to myself when I said, “Okay, I’m committed”? What would it mean if it was possible to lie to myself– to truly believe myself when I was lying? Did my commitment somehow evaporate in the moment just before I aborted? Did my body — my physical corpus separate from my mind — somehow, literally, physically refuse my mind’s directions? Is that even be possible?

Here’s another experiment I’ve performed countless times: I get set up for a jump which pushes my limits. There are some consequences to missing, some real bit of danger is present, but it’s a good jump, something I know I can do. I’ve checked my surfaces, and I’ve explored and thought out everything to look for unknown-unknowns. I’m ready. The thinking-me-brain commits — really commits — we (the me-brain and the body) are ready to do this! And then I notice that my palms are sweating. Wait- What? Who called for sweating palms?!

Therefore I’m forced to wonder: Does my body have a mind of its own? In fact, I believe this is the case. We know the brain — the entire central nervous system — is an amalgam of layers. The thinking me’s consciousness is just the topmost layer, and there are deeper layers, sometimes called the “lizard brain”, performing fully autonomous functions. Performing many autonomous functions.

After all of that thinking and experimenting, I’m starting to believe that commitment is actually easy. The thinking-me-brain is good at committing to something after a bit of reasoned consideration. Committing may be one of its greatest skills, in stark contrast to the body’s short-sighted visceral behaviors.

So what then is hard?

Learning what level of control I am in fact able to exercise over the rest of my body is hard!

My commitment evaporates when my body rebels; When it literally, physically refuses my thinking-me-brain’s commands. My commitment evaporates when unconscious triggers, and reward/feedback loops, guide my actions when the thinking-me-brain isn’t actively paying attention. The teacher leaves the classroom and the students start throwing paper airplanes. “I thought we were committed to reading our studies! …why all this fooling around?!” I thought we were committed to this jump! Why have we not jumped?! Why are our palms sweating and heart racing?!

The more I examine this situation, the more it feels like the thinking-me-brain is a tiny little prisoner who has very little control over almost nothing.

“Commit to the move,” the book says. The tiny, weak, thinking-me-brain would love to practice talking the body into doing things it doesn’t want to do. So let’s — thinking-me and the body — let’s go out and see what we can agree to commit to!

ɕ

If you’re not strong enough or flexible enough to do the things you love, you absolutely need to spend time working on that. But for well-rounded physical performance–not to mention the ability to apply the strength, mobility, and conditioning you’re building–it’s important to work on your motor control and coordination as well.

~ Jarlo from, The Key to Better Performance: Coordination Exercises You Need to Try

slip:4ugico1.

Flexibility/range-of-motion, strength, and coordination are the big three components of healthy movement [in my opinion]. This is a great article about coordination, complex motor skills, and (inadvertently) helps explain a lot of why I love Parkour.

ɕ

Early on a brisk Saturday morning, I was struggling to find the motivation to put solid effort into a quadrapedie workout. During a break, I was talking to someone about how I’ve recently been dropping goals. I’ve always had a laundry-list of goals such as getting to a free-standing hand-stand, or a specific number of pull-ups. But I’m learning — slowly — that blindly chasing goals only leads me to injury and failure. Tenaciously refusing to let go of a goal can be counterproductive, even overtly unhealthy.

I find it’s easy to learn, and easy to get some new bit of knowledge stored in my mind. But it is difficult to get my instincts and feelings to change to align with that new knowledge. So it is with my processes and goals: I know it’s all about the process, but my instincts and habits are to create goal upon goal. I regularly get caught up chasing the goals, and lose sight of the process.

How far ahead can I see? How wisely can I set my goals? Do I chase them blindly causing my journey to veer off? Or do I have a broad spread of goals that firmly draw me in my desired direction towards the horizon, and ultimately, to the end of my journey?

ɕ

The question is, do we want parkour to be a thing that is a casual part of more people’s lifestyles, like walking a dog or riding a bike? Or do we want it to be a pursuit only the able and passionate need bother even try?

~ Amy Vhan from, «https://fallingleavesandabird.com/2016/11/29/parkour-spectacle-competition/»

ɕ

INSANE. Today is already off the chart @ppkphilly

ɕ

Humans are very efficient walkers, and a key component of being an efficient walker in all kind of mammals is having long legs,” Webber said. “Cats and dogs are up on the balls of their feet, with their heel elevated up in the air, so they’ve adapted to have a longer leg, but humans have done something different. We’ve dropped our heels down on the ground, which physically makes our legs shorter than they could be if were up on our toes, and this was a conundrum to us (scientists).

~ From Why we walk on our heels instead of our toes

slip:4upyne9.

Turns out heel-to-toe rolling gives longer *effective* leg length. Our lower legs are exquisite.

ɕ

But when they accidentally drop a pk spot, BOOM! #jumponallthethings

ɕ

Be excellent to each other!

ɕ

slip:4unabo2.

The above is a great article! It’s long, detailed, and clear. But first, think about this…

You know — intuitively — that some amount of energy goes into your legs any time you move on your feet. You know that shoes are not magic; They don’t magically consume energy making it disappear. So the energy from any impact (walk, run, jump) is still coming into your legs from the ground. Cushioned shoes TRICK your perception into feeling things are going great. In reality, the only way to control/lessen the impact on your joints is to CHANGE the mechanics of your feet, ankle, knee, stride, jump, etc.

Think of your shoes as a power tool! Those who can use a screw driver well — who fully understand everything about screws and all the features of the power screw driver — can really get a lot of quality work done with a power screw driver. Conversely, a lot of damage can be done with a power tool in unskilled hands.

ɕ

I’m working on a crazy idea as a side project. Totally unrelated, I’m reading Julie’s CinéParkour. I’m just reading along this evening, and I get to this paragraph. This is so apropos of my train of thought these past few weeks.

Mind.

Blown.

Traceurs are active subjects within dominant power relations who use parkour as a technology of the self; an active transformative tool, to create and understand themselves and move away from fixed notions of identity and behaviour. Through a process of critical thinking and self-awereness traceurs problemitise and set ethics by which they adhere to. Parkour becomes a ‘practice of libery’, where traceurs practice freedom as a lifestyle, based on inventions and styles, that create ethics centered around creative environmental interactions and connections, to reclaim the body as an autonomous vehicle, away from the dominant notion of ‘bio-power’ and other dominant discourses.

~ Julie Angel, from CinéParkour, pg 152

‘technology of the self’

‘freedom as a lifestyle’

‘ethics centered around creative environmental interactions and connections’

‘reclaim the body as an autonomous vehicle’

ɕ

yeeeeeeup!

ɕ

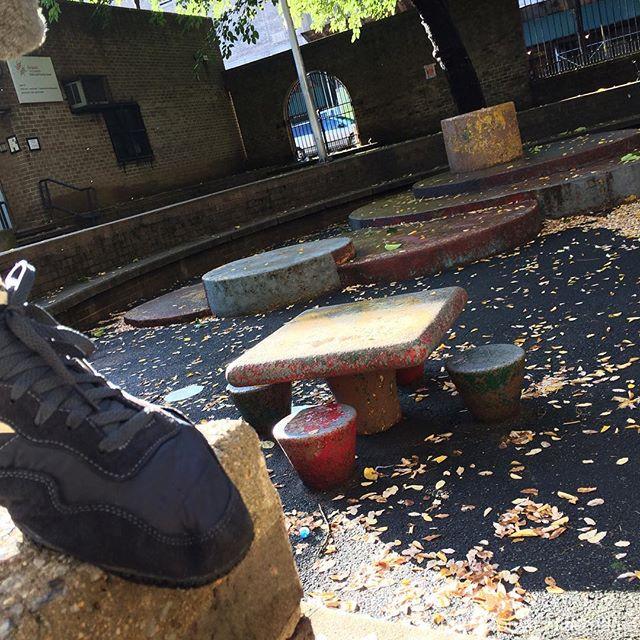

OMG. o. m. g. OH MY GAWD… Mr and Mrs Fite, thank you. A stone visionary!

ɕ

Never been here before….

ɕ

Keep on keepin’ on!: I’ve filled in the rest of the bars and this thing now needs a name. Until you’ve tried moving in a complex space, you won’t know how supremely capable the human body is; shoulders, grip, torso, knees, feet, vision, proprioception, spacial mapping… that meat-frame your mind lives in is meant to M. O. V. E.

ɕ

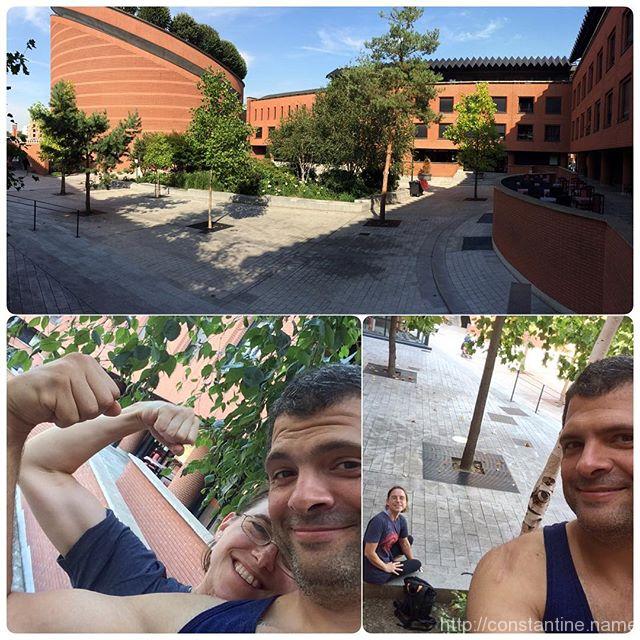

Spent all day here… push bend jump qm run vault parkour all the things!!! One more ‘section’ to go as soon as our training partner returns from a coffee run.

ɕ