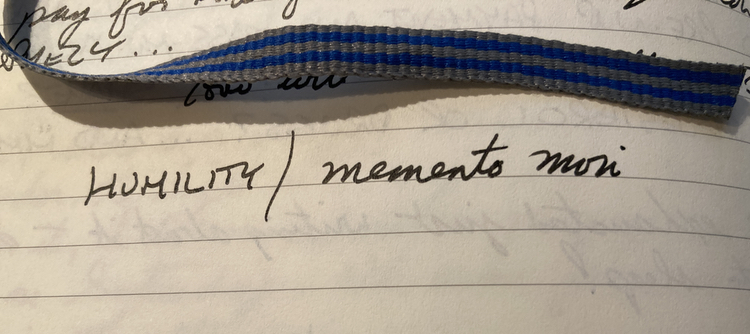

It’s become cliché to talk about finding our ‘why’. That’s a shame because it’s absolutely, still, critically important, to us as podcasters. I was recently reminded of this point…

Ask yourself, why am I podcasting as a host, or as a guest? You must have a clear why, and it should be bigger than just “me.”

~ Alex Sanfilippo

Tell me your ‘why’.

And if you just hesitated— If you don’t immediately have an answer— Then you do not actually know your ‘why’.

You don’t have to post it! But you better know exactly and clearly what it is. Posting it just puts it out there, ensuring it remains real for you.

Whether or not you post it, you absolutely must have a ready-to-mind answer for your ‘why’.

For the longest running of my shows, Movers Mindset, my why is…

Each conversation feeds my insatiable curiosity, but I share them to turn on a light for someone else, to inspire them, or to give them their next question.

When I started that show, I did not have a clear ‘why’. It wasn’t until I took the Akimbo podcasting course in 2019, that I took the time to reimagine a lot of the two-year-old Movers Mindset podcast, and prompting from the course material and the coaches turned me onto asking myself, “uh, yeah, why?!”

ɕ