I find that working in dashes is a spectacular way to make incremental progress on something. My favorite these days is a ~40-minute dash using a large sand timer. My dashes always run a few minutes over, and then accounting for time after the dash—to deal with whatever has come up—these dashes effectively consume an hour of my time. Reading, listening to podcasts I’ve curated for myself, writing, or working on outreach to invite people onto a podcast show, are all things which will never be finished. They’re perfect never-ending projects to be tackled in dashes.

I’ve been using health tracking grids, which I keep directly in my personal journals, and a tasks and project management program called OmniFocus, for over a decade. I have a long running drive to track small steps that lead to big changes or big goals. For a specific type of step, or task if you prefer, this has consistently failed miserably.

The problem is that progress on such projects doesn’t have to be do-it-every-day perfect. I simply need to do it often enough. If I have a row in my health grid, it stresses me out if I go days without ticking it off. The same happens in my tasks and projects software; A recurring to-do item for “reading” just sits there with an aging “was due on” date, adding stress. When January rolled around this year, I removed all my forever-projects from both my health tracking grid, and my tasks and projects software. Perfection, in those two systems, is now something that I can actually achieve.

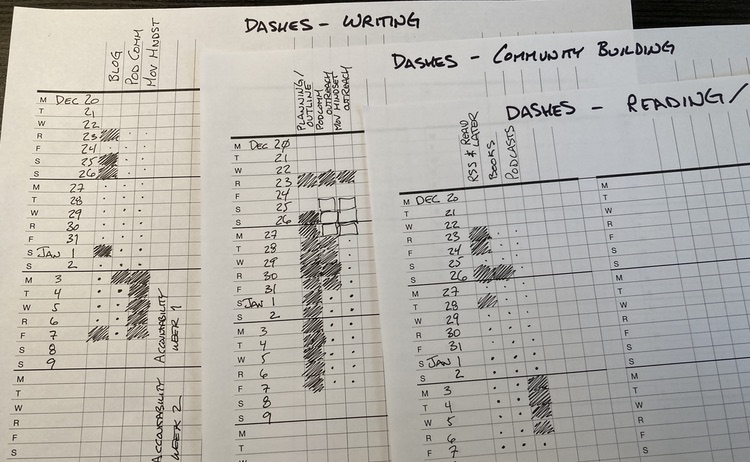

Now, what to do with the never-ending projects? I spent some time whipping up a spreadsheet of “don’t break the chain” style tracking. (This is not a new idea, I’m aware.) Here are three sheets, for three different groupings of never-ending projects: “Writing” for three different publication places; “Community Building” efforts in three different contexts; and “Reading/Listening” in three different mediums. (On one, I was drawing empty squares, but decided simple dots were fine for “didn’t do.”) I like the filled in panache of which ones are done… they are really done.

Most days, I set myself a rough list of tasks with any things at specific times marked as well, in a small notebook. The tiny size of the notebook helps remind me to not plan too much for each day. It’s an eternal struggle of course. I do not look at these sheets when I’m planning a day. I know what needs to be done—all 9 of these dashes are never-ending projects which I want to see move forward.

“I need to write some blog posts today…” goes on my day’s plan, and that’s going to be one dash, and blog writing is often much longer than 40-minutes. “I’m in an accountability session that’s part of Movers Mindset, and I’m being held accountable to write every day for that…” goes on my day’s plan as a dash. And some other things get added to my day’s plan. Then as my day goes on, I might spontaneously do some reading, or go for a walk and listen to some podcasts. At the end of the day, (or the next morning,) I pick up these sheets from where they site out of my sight and I fill the day in.

Several lessons are being taught me. 9 freakin’ dashes in a day is literally not possible; the most I’ve done is 5 so far. 2+ is the average, and 3 feels like it could really work. It’s interesting that 3 is the number, right? How often do we hear to pick no more than 3 “big rocks” to put into each day? It’s also really clear where my commitment actually falls; That “plan/outline” dash is not just a dash. I start by planning within an enormous outline document which contains all my plans for two entirely different and very large projects. And then I often spend an hour or three working on things from that plan. I should be able to get through that entire plan, and then retire that “project” from the dashes tracking.

ɕ