Today I thought I’d share a thorough explanation of what I do “to” a book these days. This process—which to be honest I don’t follow for every book I read—is the result of combining a few different ideas:

- I love the physicality of books. The typography, the paper, writing in them, desultory bookmarks, (I add my own ribbon bookmarks,) and numerous sticky-notes poking out the side.

- I love the peaceful, inertness of books. They literally sit there and do nothing. There are no alerts, and no interaction, (from anyone beyond the author’s original magic spell.)

- I’ve always wanted to retain more of the knowledge from a book once I’ve read it.

- I’ve wanted to be free of my self-imposed rule of reading every page.

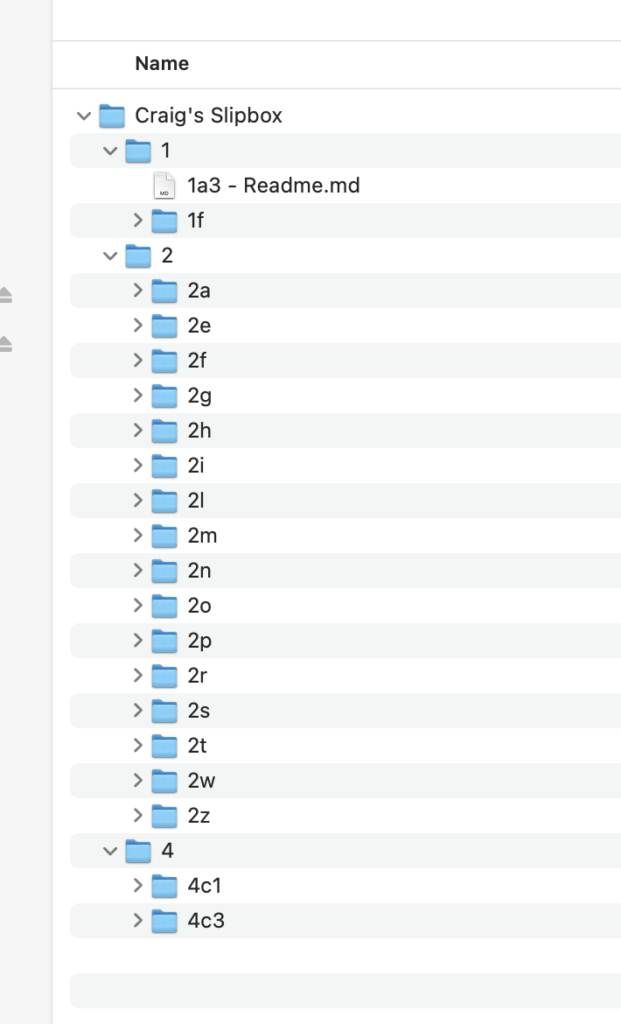

- These days I have a slipbox, and I want it to grow.

- I love to collect quotes.

- I’ve always wanted a set of crib notes, summary, or something that I could lay hand on after reading a book.

Arrival

Fortunately, books arrive slowly. It took practice, but I learned to do all of the following in a minute or two.

If it’s a new book, I take a few moments to prepare the spine. (Please tell me you know how to do that.) I affix a small, white, circular label on the spine, and I slap a sticky-note on the first face opposite the cover.

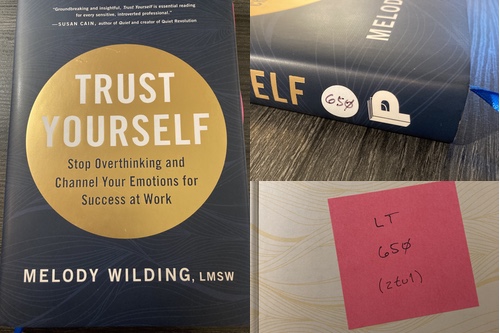

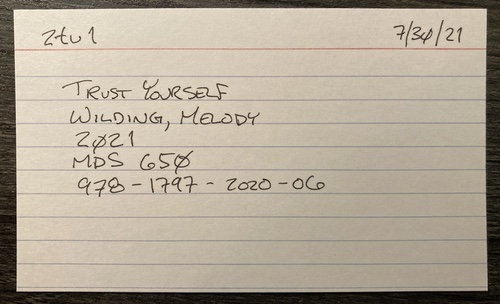

I skip over to librarything.com and find the book in “Your Books”—my books, that is. Most arriving books are coming in after already being in my “wishlist” collection; They get moved to the “library” collection. Otherwise they get searched for and added to my collection. Books get tagged as “physical,” (as opposed to those tagged “PDF,” “iBooks”, or “Kindle,” because, yeup, I track those too.) I see what MDS number Library Thing says the librarians of the world have chosen.

On the sticky-note, I write “LT”, (for “this book is entered into Library Thing,) and the MDS number. I write the main, three-digit part of the MDS number on the label on the spine.

Finally, I skip over to bookmooch.com and remove it from my Wishlist over there to ensure I don’t forget about it. (Lest I accidentally “spend” my Book Mooch points requesting a book I now have.) If this is a book that someone sent me because of Book Mooch, I hit the “Received!” button instead.

This book is now “ours.” And some amazing things are now possible just by having spent a couple minutes on each book as it arrives. (Please ignore the entire week I spent bootstrapping ~500 books when I started doing all this. :)

- Physical bookstores are fun again! What books are on my wishlist? (500+ at the moment) …okay, what wishlist books are tagged, “priority”? (about 250 — yes I have a problem.) Picking up a book… “this looks interesting…” Do I already have it in the house, maybe now is the time to buy it? Did I once have it, and it’s no longer in our collection, (part of my collections in Library Thing is “had but gone now”)?

- Long-term storage of books doesn’t mean they are lost. A big portion of the books in our house are here because we want to keep them. They sit for years untouched. Those are shelved by MDS number. Ask me for a book, and I can walk directly to it; It’s either laying about somewhere and top of mind, or it’s shelved where it can be found immediately.

- This is morbid, but if the house burned down I could decide what books to replace.

Books are for reading

Well, technically, one can also build a thing called an anti-library. But eventually, hopefully, or at least this is what I keep telling myself: I start reading the book.

I do tend to read the entire book. But generally I read the table of contents first to see what I’m getting into. If I think the book is going to be a really deep read—something I want to read more than once, refer to, and really ingest—I probably read the Afterword first. The Afterword was written dead-last, after the book was done and the author is a different person at that point. Then maybe the Foreword, or some books have a Summary, or a Preface, whatever.

I’ve no qualms about skipping parts. For example, in books like Trust Yourself by M Wilding I skipped all the anecdotes and skipped all the workbook/exercises stuff. I ended up reading only about one-third of all of the pages. (Still, a good book by the way.)

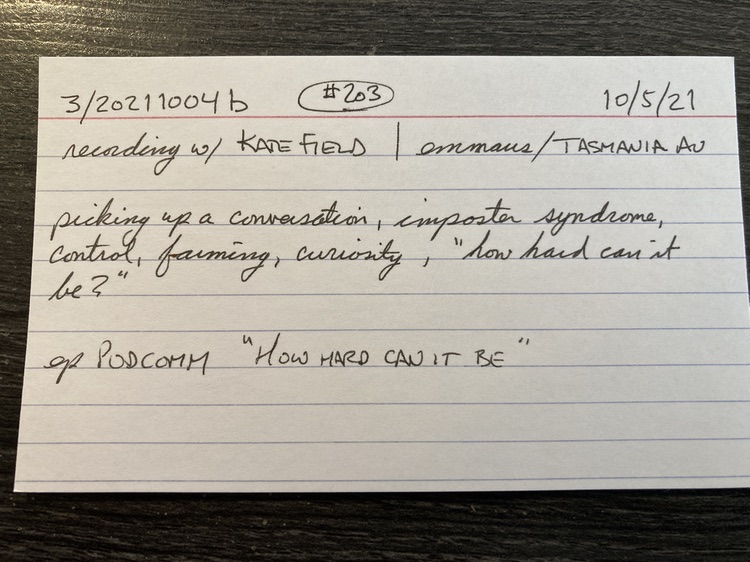

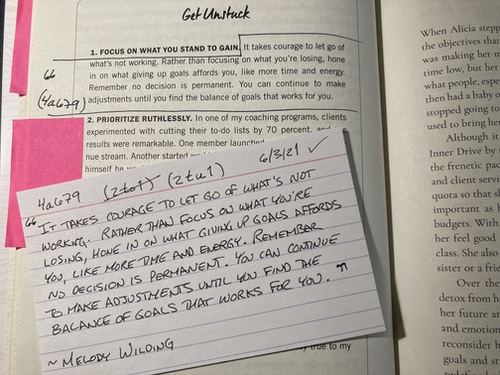

As I’m reading, if anything quotable jumps out, I’ll capture that on the spot. This leads to me making some marks, allocating a slipbox slip address, and I’ll leave a small post-it sticking out the side. I’ve never met a book worth reading that didn’t have at least one quotable bit awaiting me within.

Slipbox

As soon as the first slip gets created from the book, that slip needs to refer to the book. That means the book itself needs to be in the slipbox. Apparently, I always wanted to be a librarian.

And now I can leave a “(2tu1)” reference on the quote’s slip.

So that’s a bit of detour, but it really only takes me about a minute. You’ll notice—first photo at top—that the sticky-note for this example book has a slipbox reference, “(2tu1)”—the parens mean “this is a reference”. I didn’t put that on the sticky-note when the book arrived. That was added when I put the book into the slipbox by creating slip “2tu1”.

But mostly, I’m just reading the book.

Identify summarizing bits

One day, I’m finished reading.

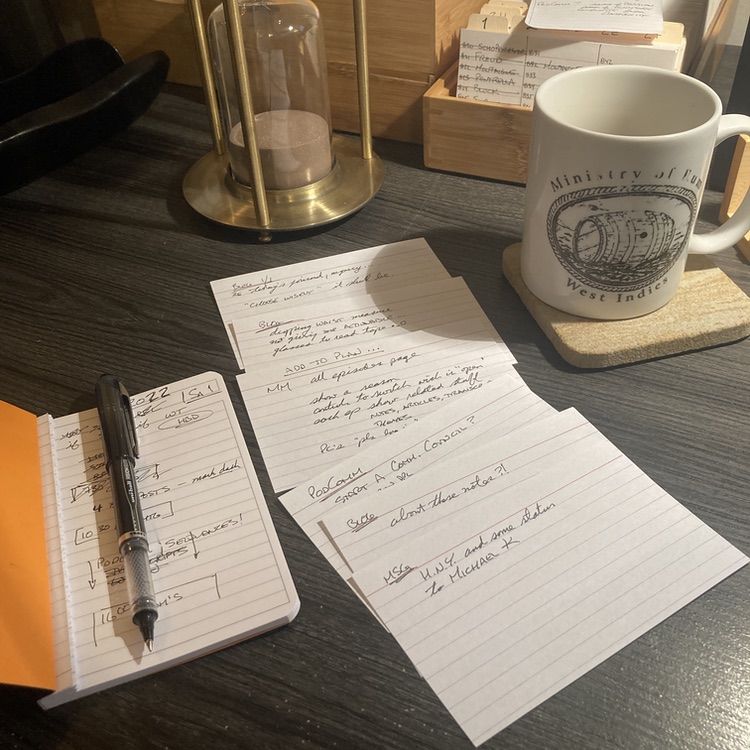

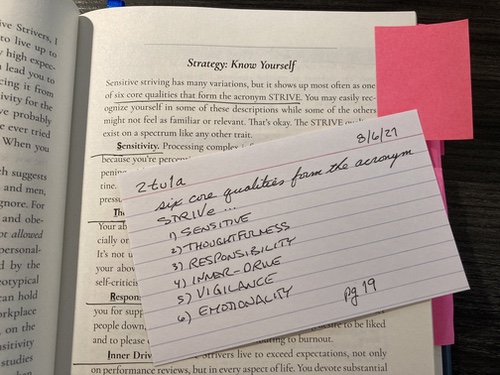

I find that even if it took me months to finish, the book’s contents remain pretty fresh in my mind. I flip through the book cover-to-cover, just skimming and noticing what I recall from reading. When I see a good, representative bit, I simply stick in a blank card at those spots. This lets me gauge how many slips my “summary” will be; Two is too few, and 20 might be too many.

Each spot has some key point that I want to include in my summary. I don’t write anything at this point. The goal is just to stick the cards into all the places that I want to include in my summary.

(I once tried using a printed template whose layout facilitated taking brief notes and had pre-printed page numbers. Folded, it doubled as a bookmark so I could build some notes as I read. When an idea leapt out, I’d find the page number on the sheet and jot a note. It was a neat idea, but didn’t work out for me.)

Summarization

Finally, I go through all the spots I’ve identified and I do a little underlining. I jot the basics of the idea on a slip and address it. So for this example book, whose slip is addressed “2tu1”, this first of the summary slips goes “below” as “2tu1a.” Next summary slip would be, “2tu1b”, “2tu1c” etc.

ɕ